Bill Tierney Then and Now: 2009 Person of the Year Interview

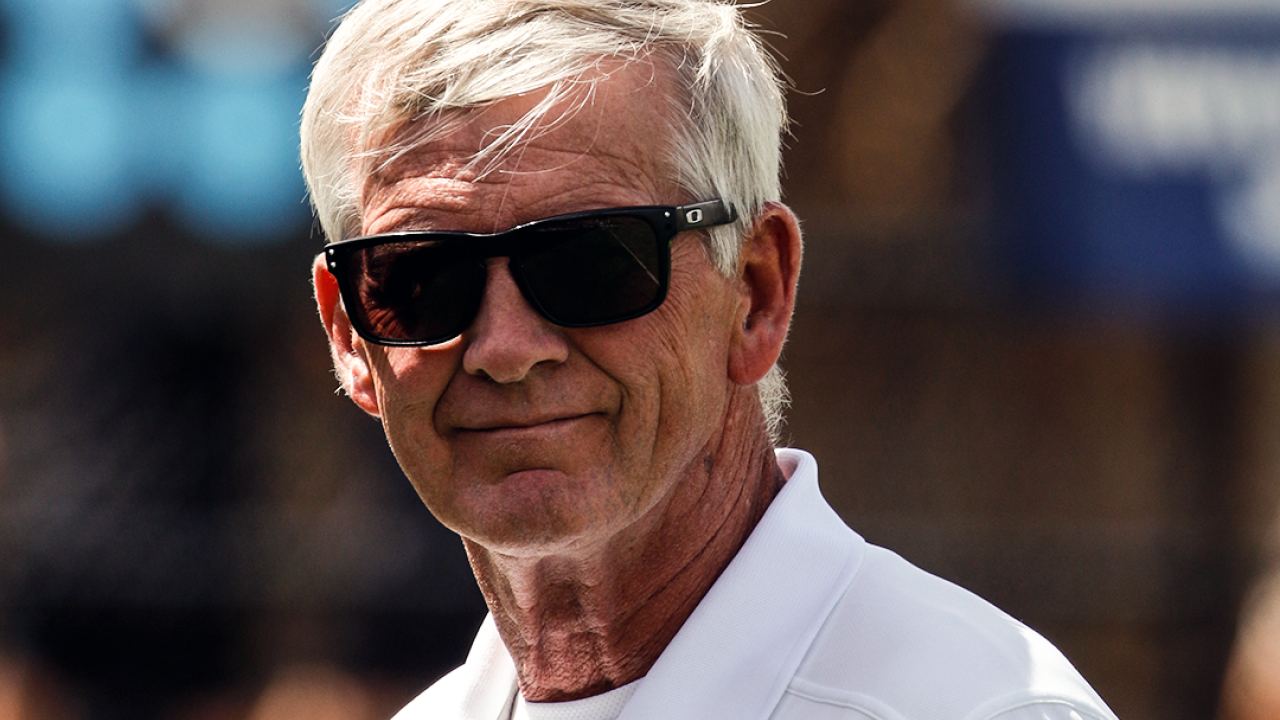

Fourteen years ago, Bill Tierney shocked the lacrosse world when he left Princeton for Denver — where he would only add to his legacy as the most decorated coach in NCAA history by leading the Pioneers to a national championship in 2015.

A seven-time national champion as a head coach, Tierney announced Thursday he’s retiring after the upcoming season. He owns a 429-147 career record and seven NCAA championships.

Here’s a look back at our 2009 Person of the Year interview with Tierney, during which the National Lacrosse Hall of Fame coach talked about his upbringing, the man behind the manic sideline eruptions and what motivated him to move west.

HIS ROOTS

Let’s go back to the beginning. How did you get involved in this racket known as lacrosse?

I went to Cortland State in upstate New York, never played high school lacrosse. My goal when I went to Cortland was that I wanted to teach phys-ed and be the head football coach at my high school, and I actually became that. My first year at Cortland my roommate was a goalie from my hometown, Levittown, New York. He talked me into starting to play lacrosse. As one reporter wrote it a long time ago, I turned into a weak-armed third baseman that found a new niche.

I played football my first year in college and got into lacrosse for four years. I really wanted to coach football when I got back to Long Island. I had played four years of lacrosse and I wanted to coach both. I got out of college in ‘73 and by ‘80 I was the head football coach and lacrosse coach at my old high school.

What made you make the jump to the college ranks?

My best friend Ray Rostan, who’s now the head coach at Hampden-Sydney, he was the head coach at RIT. It was late in the summer, late August. He called me and said, “I’m leaving RIT and going to Ithaca College.” He got named the head soccer and lacrosse coach at Ithaca College. He said, “Would you be interested in moving into college lacrosse?”

I was just starting my first year as head football coach, this dream job of mine at my high school. RIT had decided they weren’t going to move forward right away that fall. I got to coach that fall in football. Because it was a middle-of-the-year appointment, a lot of guys that probably would have gotten that job in front of me because I was a high school coach weren’t available at that point.

Somehow I was able to talk Lou Spiotti, who was the AD at RIT and still is, in the fall of ‘81 into hiring me. So I moved to Rochester with my wife Helen. Trevor was 3, Brendan was 2, and my daughter Courtney was two weeks old when we moved to Rochester, New York.

Becoming an assistant at Johns Hopkins, the pinnacle, must have been a big break for you. How did that unfold?

I did the RIT thing for three years. Then Larry Quinn, who played for me at Levittown Memorial and was an altar boy at my wedding — my parents and his parents were best of friends; he lived around the corner from me— called and said Coach [Chic] Ciccarone is leaving Hopkins and Coach [Don] Zimmerman is getting ready to be named head coach. Would you think about being an assistant here?

Of course. I applied for that job. It was weird because it was March of ‘84 and it was in the middle of their season that I got interviewed at Hopkins, but I somehow got the job. I had to fabricate myself again for another AD and had to convince Bob Scott that I could coach the soccer team at Hopkins. So I became the head soccer coach after three years prior to that being the head football coach at my high school. And that was weird, because it really catapulted me into the Princeton job. Number one, we did really well at lacrosse [at Hopkins]. In ‘85 and ‘87 we won national championships with Larry Quinn and John DeTomasso and those guys. But the soccer job turned into something that the Princeton people were very impressed with. Hopkins soccer had not had a winning season in six years, and my last two years we went 14-3 and 15-3 and made the NCAA tournament, literally in a sport that I didn’t know what I was talking about.

When I was back at RIT, my office mate was a guy named Doug May, who was a phenomenal soccer coach. My first month on the job as the Hopkins soccer coach I called Doug every day. At the end of the month, Bob Scott walks in with the phone bill and asks me who I’m calling in Rochester every day. I had to confess to him I was calling Doug to get my practice plan for the day.

When Princeton was looking for a coach was after the spring of ‘87, we had won two championships, and between the lacrosse success as an assistant at Hopkins and turning the soccer program around, they were kind of enamored by that. I was lucky to be offered that job. I was 36 years old. I kind of went there blindly. My goal was to someday be the head coach at Hopkins, Virginia, one of those places. Three years later I was offered the Hopkins job, when Zim left. I turned it down and stayed at Princeton for 22 years.

Fourteen years ago, Bill Tierney shocked lacrosse when he left Princeton for Denver — where he added to his legacy as the most decorated coach in NCAA history.

— USA Lacrosse Magazine (@USALacrosseMag) January 6, 2023

The 2009 USA Lacrosse Mag Person of the Year and 7-time NCAA champ announced Thursday he's retiring after the season. pic.twitter.com/SgFrtQ1IhI

Why’d you turn that down?

I love Bob Scott. I love the institution. It was everything I ever wanted to be. I’ll never forget driving back to Princeton with my wife. She had been following me around all these years. It was 1990. We had just beaten Hopkins in the tournament. We lost to them in the regular season 20-8 and beat ‘em in the tournament 9-8. That was the first NCAA tournament game at Princeton and our first NCAA tournament win ever. With that next group coming in — we had just recruited Scott Bacigalupo, Kevin Lowe, all these phenomenal guys — my wife said, “You know you’re going to be pretty good at Princeton.” We kind of felt like, hey, maybe this is something we need to be our program.

I can’t believe I called Bob Scott and told him I wouldn’t take the Hopkins job. It was crazy. Thankfully, things turned out for us at Princeton the way they did and over the years I was offered a few other jobs, but I just kind of stuck with Princeton and was happy that I did.

Amidst all the twists and turns, it seems coaching was the tunnel vision. Was there a calling?

I loved sports from the time I was little. I had two older brothers and an older sister who was a phenomenal athlete. Being successful in little league sports, football, baseball and basketball, I was trying to find a way to do that. My sister went to Springfield to become a phys-ed teacher, and she wanted to be a coach. That kind of clinked in my head.

The reason I went to Cortland instead of Springfield was because at the time, Cortland was $2,000 a year and Springfield was $2,900, and I was trying to save money. My dad was a beer truck driver and my mom was a nurse. I was trying to save them some money. Thank God I went to Cortland. I never would have played lacrosse at Springfield.

It was a calling I had. I can remember back to midget football coaches and little league baseball coaches — guys that I really looked up to — then my high school football coach and all those guys I looked up to so much, it just made me know that’s what I wanted to do.

I never thought about the college thing until Ray had called me.

You grew up in Levittown, which was a pretty interesting time on Long Island and in the U.S. That was the genesis of suburbia. What was your upbringing like?

I was born in 1951. Levittown was started right after World War II in 1947. They were building hundreds of homes a day. It turned out 17,000 homes and 70,000 people in a matter of five years. It was all the GIs coming back from World War II. The prediction for it was that it was going to turn into a slum. All they did was clear out farmland.

It was such an amazing place to grow up. My block had something like 22 houses and 48 kids on the block — all squished in those baby-boomer ages. My brother was born in ‘42, my younger sister was born in ‘56. Our family had five kids. That was kind of a microcosm of what was going on there. Everybody there was a teacher, a nurse, a truck driver, a bricklayer, a plumber — all those things. It was really a neat place to grow up, a real honest place to grow up. Nobody had much; everybody was the same. Nobody’s dads were rich. Nobody was poor. You could walk into anybody’s house on the block and have peanut butter and jelly on the table for lunch. You didn’t have to worry about crime. Everybody’s doors were open.

Cortland was kind of a continuation of that. It was a teachers college. The lacrosse guys were a lot of New York and Long Island guys. I hadn’t seen anything much different. My first lacrosse coaching job was at Great Neck.

What kind of player were you at Cortland?

Not great. I started my freshman year. The beauty back then was that they had freshman teams. My freshman year there were six or seven guys who had played lacrosse before and 20 on the team. You had to play. I was a starting attackman, led the team in assists my freshman year.

My sophomore year I made the varsity and Jack Emmer was the coach back then. I made the varsity, sat on the bench. Made the varsity again my junior year, and sat on the bench, because we had four All-American attackmen in front of us.

Ray and I were seniors together, and we won a national championship that year. It was a great experience. I was not a great player. But I think not being a great player made me a better coach. As a senior, Chuch Winters was my coach. I was really upset I didn’t play much in our Cornell game. We lost 5-4. This was gonna be my year. All I wanted to do was play. He said to me, “This is going to make you a better coach.” At the time I didn’t give a crap about being a better coach; I wanted to be a player. He worked out a rotation for four or five attackmen. There was one freshman, Judd Smith, who was better than all of us. He played all the time and the other four of us rotated. I was OK. I actually became a better lacrosse player in the two years after that. The NLL had a precursor to it. The old NLL — 1974-75; Google it; it’s got some funny stuff on it — Ray and I were the only two Americans on the Rochester team. We came back to Long Island and played for the Long Island Tomahawks. My better lacrosse playing days were club lacrosse and in box lacrosse. But Chuck was right. Being on the bench a lot and hearing these phenomenal coaches, I did learn more about the game being on the scout team and getting beat up every day. I knew I wanted to coach. Having phenomenal coaches like that really helped catapult my lacrosse experience.

On or off the field, what’s the greatest adversity you have ever faced?

It’s hard to say. Certainly, I remember in coaching, the hardest thing I ever did was go 2-13 my first year at Princeton. I thought I could change the world overnight. That was really difficult. I came home from our Dartmouth game at the end of that season. It was a late road trip. Every night before I go to bed I have a cup of hot tea. I opened up the cabinet, and there’s this quote on the cabinet. My wife got it out of a sports page. It said, “We’ll be back next year, and we’ll be better.” I kind of went, “Whoa, where does that come from?” We’d been married 12 years or so, and she knew that was the motivator to kind of keep that going. We knew we had that great recruiting class coming in, but things like that help you overcome adversity.

To this point, certainly the death of my dad at too young an age was really pertinent in my life. I was 22 years old. He was a tough guy, a beer truck driver, smoked three packs a day, drank beer — the whole bit. He died of cancer. It wasn’t like we were best friends, but it changed my life. Because the last year of his life, I was living at home alone. I had come back from college. It was just him, me and my mom. We became really close in that last year. It helped me, even in those years when I was away a lot and probably wasn’t there enough for my kids, realize how important it is to be a father. That’s clearly the most important thing.

METHOD TO HIS MADNESS

You came up coaching in the high school ranks. John Danowski, when he was named Person of the Year in 2007, lamented that a lot of young coaches today don’t follow that same path as many pioneers of the profession did. What do you make of that?

John and I talk every couple of weeks. We’re good friends. I was talking to him late last night. I think there’s a lot of truth to it. I think it comes from the teaching aspect. What happens now, guys that were great players become great coaches. I think that’s hard. That’s why I admire so much what Dave Pietramala has done at Hopkins. He never had that kind of educational background. It’s very hard for a great player to become a great coach, because he hasn’t been on the bench. It was easy for those guys to play. So to then step back and teach kids that aren’t as talented is difficult.

I agree with John. When you go through the education courses, you learn a lot about part-to-whole methods, whole-to-part methods, repeating a question when somebody asks it as opposed to turning and looking at that person, visual learning versus active learning, the art of review, repetition of skill — all these kinds of things that had nothing to do with lacrosse, but had to do with teaching. Once you combine a good teacher with a good coach — a guy like John Wooden, who could have coached anything — you’ve got a good mix there.

A lot of these guys try to be head coaches, but it’s a tough way to the top. Dave Cottle, Tony Seaman, John Danowski, Dave Urick — they’re all teachers first. Although you do see guys like Dom Starsia and Dave Pietramala — they’ve found the right spot conducive to their style of coaching. But it is hard for some of these young guys. It’s a tough profession out there. That’s why I hope to be a mentor to all the guys I’ve coached over the years.

Speaking of style, what is your style? We see the guy yelling at refs. There’s got to be more to you than that.

You hope so. If you talk to the people who know me best — Dave Metzbower, my son Trevor, Kevin Lowe, guys who played for me — they would tell you that that’s the anomaly, what the public sees.

I go back to my childhood. My dad was a yeller and a screamer. He’d be the one to tell you you’re in your room for a month. And then my mom within two hours would come up and tell you, “OK, you’re punishment’s over.” That’s how I am. I can see a direct relationship to that. I see the hardness, sometimes cruelty to players. Some of the things my ex-players tell me I said to them, I’ll tell them I never said that, and they’ll say, “Oh yeah, you did.” And yet, I think each one would tell you I always talked about loving them. I was always personal with them. I was always there for them. That’s what you see. Not sure they would say softness, but certainly kindness and love is an integral part of that.

David Morrow, I remember in a story in Lacrosse Magazine, started out by saying “I hated Bill Tierney when I got to Princeton.” It was bold. But if you read on, it was all true. Everything he said was exactly true.

What you see isn’t what you get. I’m a stickler. I’m Type A. I can’t go to bed on a Friday night if I don’t think my team is prepared. What happens on Saturday, the reason there’s that madness, so to speak, is that I feel like if we’re prepared, there’s almost nothing else to do. You don’t have to coach them on Saturday if you prepare them.

This quote I’ve had for a couple of years now from an article on Coach [Bill] Parcells in Sports Illustrated a couple years ago, it tells it all about guys like me with coaching. I’ve sent this to some young coaches.

[Reading the quote] “You wake up each morning knowing the next game is all that matters. If you fail in it, nothing you’ve done with your life counts. By your very nature, you always have to start over again fresh. It’s an uncomfortable feeling, but nonetheless addictive. Even if everyone around you tells you you’re a success, you seek out that uncomfortable place and if you don’t, you’re automatically on the wrong side of the thin curve that separates winners from losers.”

That really tells what a lot of successful coaches are about. It certainly tells my story. Stuff like this, honors and accolades, Hall of Fames, makes me somewhat uncomfortable. And I think you should be that. The other quote I have up here I’ve used in my speech when I got inducted in 2002 to the US Lacrosse Hall of Fame. My associate AD at Princeton had this quote: “Judge your success by what you had to give up in order to get it.” I twisted that a little bit around. “Judge your success by what others had to give up in order for you to get it.” I was thanking my wife, my kids, my family, my brothers and sisters, my parents. I’ve always had this crazy passion about sports. I know bringing up four kids could not have been easy, because I wasn’t there very much. And for the kids to have me helping raise other people’s kids — while I was ignoring them, so to speak — it’s kind of weird. Those are the kinds of things that have driven me in this whole coaching thing.

It’s rare you can find the exact words, but those are the ones that put it together the best for me.

It’s funny, the Parcells article quote about others calling you a success, and that you’re not comfortable unless you’re uncomfortable — did you think you were getting too comfortable at Princeton? Is this your uncomfortable place, Denver?

It might be. I hadn’t thought about it that way. Now that you ask, it might be. Funny, before I went to Princeton, I had never been anywhere more than three years. Not one job for more than three years. I was at RIT for three years and at Hopkins for three years. I kind of thought I was going to Princeton for three years. Uncomfortable at Princeton? That could never be true. I could go back there this second, live my life there –— the people, the experience, the place, it was incredible.

But as you mention it, maybe I am seeking out that uncomfortable-ness of a new team. I’ve never been afraid of high expectations at all. One of my personal things over the years was to transform fear of failure to fear of success. In athletics, it’s OK to fear failure, because a lot of people fail in athletics. It’s when you’re successful that you then set the bar higher, and then your expectations are higher, and then you have to work a lot harder. I think a lot of kids that play the game, deep down they might not want to be that successful, because it means the next day, they’re called to a higher level.

I don’t look at the six championships other than with a great deal of pride and thanks to all those people that made them possible.

Maybe that’s a part of this thing. There were two things I always said if I was ever to leave Princeton: I would leave it better than I found it — I think that’s true. And I would leave the cupboard full — I think that’s true. I have no regrets about that, and I feel good about that. But maybe part of this thing — other than what you’ve read out there with me and Trevor and the Colorado thing and the idea of giving it one more time around with a different program, all of which is true — but maybe deep down, that’s a little deeper. Maybe I have that need to do this. Twenty-two years is a long time to be with one program. Fifty-eight years is a long time to be healthy and happy and thankful. So why not give it a final shot?

THE PRINCETON YEARS

Many wouldn’t know that Princeton wasn’t very good when you overtook it. Talk about a bare cupboard. What was the state of Princeton lacrosse when you arrived there?

I got there in the summer of ‘87. One of the reasons I was inspired to take the job was that the athletic director at the time reminded me that Princeton had a great history of lacrosse. Prior to that recent history, when the Ivy League started, they won almost every Ivy League championship until the ‘70s, and then it just dropped off the face of the earth. Mike Hanna, who’s now the AD at Hobart, kind of got it back to a certain point, and then for whatever reason it just didn’t work.

Everything changed. You had to get out there recruiting. The coach there before me was one of the greatest coaches to ever coach lacrosse — Jerry Schmidt. He was a big-time coach at Hobart, won national championships, great coach, great guy, great player at Hopkins, only lacrosse player to be on the cover of Sports Illustrated, phenomenal man... But at that time in his career, things were changing at such a rapid pace with recruiting. And admissions with Princeton was hard when other schools were starting to give out scholarships.

Bob Myslik, the AD at Princeton then, said: Look, we’re on hard times now. But Hopkins soccer had not won in years; RIT lacrosse had never made it to the NCAA tournament; the Great Neck South program, where I first coached, made it further than any team there; my Levittown-Memorial team that Larry Quinn was the goalie on, we made it to the county championship — I had kind of built a reputation of turning things around.

I wasn’t afraid of it. I felt like I had a formula for it. One of the formulas was to go out, work your tail off recruiting and find kids that came from winning programs. So that’s what I set out to do. Princeton had won three or four Ivy games in four or five years. They were 1-13, 2-14 — they just weren’t doing very well. Like all those jobs I took, there was only one way to go, and that was up. I felt good about that, and felt like we could get it done.

I told those freshmen that we could win a national championship. I didn’t think we could. My goal was to get the next great job, at one of those programs that could win a national championship.

It was easier in the ‘90s than it is now. Less players, less schools giving out scholarships. Now there are so many great coaches. Film work, scouting, breaking everything down — it’s become so intricate. I think I was just lucky to be at a place that nobody else respected and come on the scene very quickly, surprise people before they knew what hit them, and then we got on a roll.

I’ve always said that there are two reasons a kid goes to a school — one is to start as freshmen, and the other is that they want to go to a good team. We kind of converged those things. When I was recruiting those first couple of classes, I told them, “You can all start as freshmen.” We were terrible. If you’re any good whatsoever, you’re going to start as a freshman. And then we got good, and we could turn quickly over into, “Hey, you can win a national championship. Why don’t you come? We started out three years ago, and now we’re in the tournament beating good teams. We’re going to get better.”

The makings of a good program were there. The foundation was there. There’s not many sports in the Ivy League that you can win a national championship in. You’re not going to win in basketball. They’re too stifled. Your best basketball players aren’t thinking Princeton when they’re 15 and 16 years old. Football, they’re not allowed to. You can’t play USC in football. There were very few sports in which you could win a national championship. Once we convinced them that we could — with the help of Cornell and Penn being in the final four; Brown was good; Harvard was good — not only win an Ivy League championship, but win in the tournament, they looked at me and said, “OK, well, let’s win a few games first.”

We did that, and it just happened so quickly.

Princeton in 1988; Denver in 2009. Can you make any correlation?

Yeah, we’re trying to do that. The only difference is we’re a lot better right now. I’m thankful for Jamie Munro and Jon Torpey and Matt Brown, who’s still with us, for providing me with so many great players that are here right now. We are in a lot better shape right now than we were in Princeton in 1988.

When we won our championship in ‘92, only Hopkins, Syracuse and North Carolina, and Cornell before that, had won it. There’s only seven that have won championships. The big mystery in lacrosse is, who’s number eight? There have been a lot of teams that have come close.

But certainly, there’s a lot of similarities to what I was doing then to what I’m doing now. That’s what I’m telling the kids. Shoot for the stars. You’d be amazed at what you can achieve if you just set your goals high.

So many young men have come under you and learned from you. Is there any individual that stands out as a success story, of whom you’re most proud?

There’s so many that you can go back to. And they’re at different levels. Take a guy like Scott Bagicalupo that comes out of St. Paul’s and is a valedictorian, best goalie in the country, in my estimation one of the best that’s ever played the game. He comes to Princeton and does really well. Four-time All-American, three-time first team All-American, two-time MVP of national championships — I didn’t do that. That’s a story unto itself, just being thankful for the fact that he came to us and he made us look better. And yet, Scott will still say at Merrill Lynch on Wall Street that he harkens back to some of the lessons he learned at Princeton through me. I look at that and say that’s ridiculous. This kid started out as a superstar and ended as a superstar.

We’ve had poor kids, superstars, guys that overcame great odds, walk-ons that became great players, kids that overcome health issues. I’ve got a kid right now, Drew Babb — the top-ranked recruit as Denver’s best midfielder. He got diagnosed in August with Hodgkin’s disease. So he can’t play this year. He’s going through chemotherapy as we speak. He’s going to be a success story. Four years from now, ask me. He’ll be a success story. He’s going to redshirt this year, with what the chemo is doing to his body. But they say he’s going to be fine.

I never had a kid write me or call me back after he graduated thanking me for being too easy on him. That’s what drives you. Those things you do to push kids to is what makes them better. Even if the kid’s not a player — I know what it’s like not to be a great player; I experienced that — it might be that walk-on that you kept that just loved the program.

There’s the famous story in 1996 of Pancho Gutstein, being our backup goalie all year. Patrick Cairns being our starter, me pulling Patrick in the semifinals and putting Pancho in and us beating Syracuse — and then doing it again on Monday against Virginia. Pancho saving a ball with his foot and being named to the All-Tournament Team. The only reason he was at Princeton was because his twin sister was a great player and she was recruited by our program. He got in too. Those kind of things are neat.

All that stuff, the big picture. What do you say? What you do? You say some ridiculous things. The ‘92 guys, when they were freshmen as my first recruiting class, they say I kept them in this room after this meeting and I said, “You guys are gonna win a national championship.” Yeah? The team had just gone 2-13. But they were. When they were seniors they were national champions.

We had a kid on that team named Evan Garfein. I was going to cut him. He was a great kid, but not a great player. The guys came to me and said, “Coach, keep him. He’s a good guy. He’s a friend of ours.” So Evan came in before his senior year and I told him, “You’re not gonna play. You’ve been wonderful for this program. You’re a wonderful guy. Just enjoy the experience.” But I said, “I’ll make you a deal. If we make it to the national championship game, I’ll let you play man-up on the first penalty.” We had beaten Carolina in the final four. He taps me on the shoulder and says, “Remember your promise?” I couldn’t have been happier — we just beat North Carolina, that had won the championship the year before. I didn’t remember anything from two weeks ago. I said, “What are you talking about?” “You made me a promise that in the championship game, I’d play on the first man-up.” I’m thinking, “You gotta be kidding me. I said that?” Sure enough, playing Syracuse on Monday, first man-up, I float the big guy out there. He’s now a surgeon. Give him credit, he takes a shot. He was at the top middle of a three-three, takes a shot and tries to squeeze it past the goalie. It sails over, we lose the ball, he comes off. He looks at me, I look at him and that’s it. We win that game, and the kid has that forever.

Too many success stories. The one closest to my heart is my son Brendan. He was an undersized attackman who a lot of people doubted should be on our team or even in D-I lacrosse. I don’t know if he made it over 145 pounds. His sophomore year, BJ Prager blew his knee out. So he wound up starting on attack for us in the semifinal and, in the championship game, he scores the winning goal against Virginia. Amazing story. He’s my favorite Tiger. Yeah, he’s my son, but more of his story, that “I’m gonna make this thing and we’re gonna do this together.” There have been a lot of those guys over the years. It’s been a blessing. I just hope I have a few more of those stories the next five or 10 years to round this thing up.

BEHIND THE DECISION

Any decision you make, people are going to put their take on it. Your name carries that value in the lacrosse world. We were canvassing some people, including some of your peers. Many were on board by saying this was a good thing for lacrosse, but you do have naysayers. I’m going to read you verbatim one of the responses we got, because I’d love to hear your response… “He is not going to Denver to help expand the game. He is racing out of the Ivy League because he no longer has every advantage in admissions and recruiting, and he cannot guarantee winning any longer…”

You never know who those people are, because they’re so weak, they never put their name on it. That’s my only problem with those forums. If that was a man saying that, he would call me and say that to me. That’s what bothers me. I laugh at that. Because the real truth of that goes back to my statement about fear of success versus fear of failure. I’m not afraid to compete in the Ivy League or of Jeff Tambroni, who’s probably one of the only coaches in the country that has a winning record against me. Jeff’s a friend; he’s a wonderful coach. I’m not afraid of those great, great games between Cornell and Princeton.

People think that I went to Princeton and fell into open arms, like admissions opened the doors for us. What I learned a long time ago is, wherever we go, you take advantage of what’s special about that school. Princeton University is no doubt the finest undergraduate educational institution in the world. The only thing I did there is, I found people who understood that. They also were pretty good lacrosse players, wanting to follow me and my vision for what they could be.

If people think that after 22 years I’m running away from young coaches, that’s absurd. Do they think that they just opened the doors for us there? Do they think if they did that I would have graduated every person that ever came to me in 22 years in Princeton — on time? Think those guys would have completed a thesis — an 80- to 100-page book that every student there has to do? Ever think about the sacrifices that some of those guys and their families gave up to turn down full scholarships and pay up to $200,000 over four years? You don’t make that back in your career very quickly. They could have gone to nicer weather, nicer facility, the hype of ACC schools — whatever it might be. Every one of those guys made me stronger.

If there’s anybody out there thinking I was running away, if they know Bill Tierney, they’ll know that the tougher the situation, the more he’d look forward to it, as opposed to running away from it.

If I was running away from tough situations, I would have never gone to RIT in January with a wife and three kids. I would have never gone to be the head soccer coach at a place where they seldom had a winning season in 50 years. I would never have come to Princeton, which was clearly abysmal in lacrosse. They’re talking about a different guy.

The reasons I’ve come to Denver are all positive reasons. I’m not running away from anything. How can you run away from one of the greatest places on earth to live, one of the greatest schools on earth, being a part of probably 250 young men’s lives and some of the finest people on earth and with them so vehemently through the ups and downs? It’s absurd, and it shows the absurdity of someone who won’t put his name on something

What was the linchpin moment for you to make this decision, when you went into “yes” mode?

I came in here in “no” mode. Peg (DU athletic director Peg Bradley-Doppes) said to me, “Just come out. Spend two days with us. And if you walk away and say, ‘No thanks, I’m happy where I’m at and it’s not right for me,’ we’ll just thank you for being here for two days. It’ll give us some insight on who we should hire, some insight on what it’s going to take to get to the next level, and we’ll be kind of thankful for that.”

And that was kind of my first thought. “Whoa. They’re not saying, ‘This is the greatest. You’ve got to come here.’ So I said, yeah, I’ll come for two days. It’s a beautiful place, and I could come and see my son Trevor for a couple of days. That’s kind of the way I did it.

Then, everything I went through on my interview here — the people that I met or the situation — every time I walked away from it, it said “yes” to me. Rob Grahame, our associate AD, took me out to meet Pat Bowlen, who owns the Denver Broncos. Pat Bowlen didn’t sit there flaunting his money at me or telling me how great he was. Pat Bowlen sat there and said, “Coach, I love lacrosse. And you tell me what you want to have me do to help your program get better.” And I’m like, “Whoa.” That’s unbelievable.

Then coming back here and meeting Todd Rinehart our admissions guy, who said, “Coach, we’re trying to make this a better school. We don’t want you to look at it as a place where you can get anyone you want in. We want you to bring in the type of students you brought to Princeton, and work together on this thing.”

Going out with Peg on her balcony overlooking Barton Stadium, and she’s saying, “Isn’t it a beautiful lacrosse stadium?” By then, I’m starting to think “maybe” on this thing. And I said, “Well, if I come, we’re going to make that stadium obsolete. It’s going to have to be bigger.”

Everything kept coming up. It was the second morning. I was supposed to be here at 9 o’clock, and I get a call at Trevor’s place at about 6:30 saying, “You better hurry up, we’re going someplace at a quarter to 7.” So we get going, and where do they bring me? To the board of trustees. I’m meeting the 40 most powerful people, the chancellor, and they all say to me – this is board of trustees, the people that are deciding on the future of the place, not just some athletic director – that they really want this thing to go. And that’s what got me excited.

On the way home Friday night I said I have to clear this with some very important people. Trevor’s last words he said to me when I got on the plane were, “Do this for yourself. Don’t do this for me.” I got home and it was late. I got in bed, and my wife just said, “Well, whaddya think?” At that moment I said, “Well, I think I’m gonna do this.”

The next morning I called my associate AD Mike Cross, who’s my buddy. I said, “Mike, I need to see ya.” He said, “On a Saturday morning at 8?” “Yeah.” “What’s this all about?” “I need to see ya.” Later on he told me he thought one of my players got in trouble. We met at a coffee shop and it kind of went from there. I talked to my AD that afternoon. I talked to the president the next day.

Everybody was saying the Princeton people must have been in shock. Certainly they were, but so were the Denver people and, most importantly, so was I — because I wasn’t looking for it, because I wasn’t searching, because I was happy, thrilled to be at Princeton. We had just come off a 13-3 season, a couple goals short of a final four, kids were phenomenal, great team coming back. There was no reason to leave there. When all that came together and I said yes, I knew I meant yes.

What about the money element?

The naysayers should know, and this is the first I’m going to make this public, is I took a cut to come here. All that word out there about me making $2 million and all that stuff is false. I had a very established camp situation at Princeton. I was probably the top-paid lacrosse coach in the country at Princeton. If I wasn’t, I was certainly close. And I probably still am. [Denver] had to dig deep to get me to come to a spot where I was taking a pay cut. Princeton had a situation with its housing. When I got the job at Princeton, they invested in one-third of my house and loaned me another third. I only had to pay for one-third of my house at Princeton. There’s no program like that here.

And so if people think this is for money, they’re out of their minds. Now I am still in business with Tony Seaman and Dave Cottle with Top 205 camps; we’re going to build our camps out here. I’m in business with three young guys who need money. After 30 years of being married, I was finally able to invest in a beach house on the Jersey shore. I’ve still got that to pay for.

Anybody who thinks I did this for money, again, they don’t know me.

This is not about money. In fact, it’s significantly different right now. Hopefully as we build this thing and we’ve started a little company here doing camps and clinics, hopefully we’ll get some of that back. But believe me, it’s not about money. For ease of economics, if I’d have stayed at Princeton, it would have been a lot easier.

The term?

Five years. I told them the same exact thing I told Bob Myslik back in 1987: Give me a one-year contract. That’s all I want. At Princeton, they laughed at me and gave me three. Here, they laughed at me and gave me five. I think a coach should be judged at the end of every year. Not that a great coach can’t have a bad year. I think if you look at the recent history of lacrosse, you’ll see that Dave Pietramala had a five-loss season last year, God forbid, for a guy who probably will go down as the greatest coach in the history of the game. Dom Starsia had a losing season some years back; John Desko had a losing season some years back. These are the finest coaches in the game. That can happen.

But if there’s a consistency in losing, then the coach should be fired.

How were you able to keep this so well under wraps?

One of the things that happened was, like a lot of jobs, people here called me to help them with their search. There’s a lot of young coaches that put me as a reference on their applications. What I always tell them is, look, I’d be glad to be a reference on your application, but you should also know that Tom, Dick and Harry — I’m on their resumes as well.

The school usually calls me and says, “Look Bill, we’ve got five guys here we think are great candidates, and they all have your name on this. Can we talk to you about it?”

That’s how it all started. And then eventually Pam Wettig, our associate AD here who was running the search said, “What would it take to get you here?” I started laughing. I said, “Pam, you can’t afford me. It’s just too good for me at Princeton.” Then she said, “Well, what would make you consider it?” I probably gave her the crack she was looking for. It was, “Well, if I ever took another job, it would be out west, because that’s where I want to retire.”

In the next hour Peg called. The boss called. She said, “What’s it gonna take?” The way they ran the normal search the week or so before was they brought three coaches out here, put them all in a hotel, interviewed for two hours, saw each other on campus. I said, “Peg, I cannot do that. I just can’t afford to have people at Princeton think that I’m searching something out, because I’m not.” So she said, “How about we bring you out on your own next week? Come Thursday, Friday, just come visit us.” That’s what we did, and then that weekend was the time. I knew I had to make a decision quickly. And it was hard to do that because I had not much time to think. When you’re leaving something that’s so good, you’re fearful that you’re making a mistake. But I made it. It was under wraps. People here did a good job keeping it under wraps. And to be honest, even my dear friends that knew I was coming out here — Dave Cottle, Tony Seaman, those guys — didn’t know.

I turned down the Hopkins job three times. I turned down the Virginia job. I turned down the Army job. Those are three pretty prestigious places. I think of the people that know me the best thought, “OK, he’s going to go out there and talk to them a bit, but even if they offer him the job, he’s going to turn it down anyway. He’s turned down these other jobs. Why would he go to Denver, for God’s sake?”

That’s what made it so exciting. That’s what made it good. I knew I didn’t need the job. I think that’s what convinced me so much that it was the right decision.

HIS LEGACY

How has this experience changed you?

Everybody talks about, why did I come here? But for [Denver] to take a chance on a 58-year-old guy, what do they know? I might just be on the downswing. I might just be looking for a place to retire, as my friends on LaxPower have said. I’m not, but what do they know? They’ve taken much more of a chance than I am. I’m at a place that’s only 11 years into Division I. The whole place is new. You’ve got the support of people like Laura Barton, building this kind of stadium. It’s been really amazing and really overwhelming now that I’m here. The happiness I experience every day to come into this office and work with these three guys (assistants Matt Brown, Trevor Tierney and Kevin Unterstein) is amazing. I’ve been very blessed over the years to work with very loyal guys.

Usually when you hire a new head coach, it’s someone younger. Here I come in, and I’ve got all these ways I do things. I’m hoping that I’m not upsetting any apple carts or doing too many things the wrong way, because I just want to fit in. I want to mold our team to be like our hockey team, which has won two national championships the last five years. I want us to fit right in. One of the reasons I moved our offices back [into the Ritchie Center, from Barton Stadium] is because I want our promotions people, our sports information people to feel like they’re totally engulfed in the whole athletic program. I’ve learned over the years that isolating yourself in one sport is not good. You don’t benefit from it. It’s like they always say when we do community service things. You think you’re going to help underprivileged kids, but you get more out of it than they do. That’s how I feel here. I just hope they feel it was worth the investment to have me come in and help get this thing on track.

What about here at Denver, your to-do list here? You inherited discipline problems, with three players that were dismissed from the team last year and others who fell out of favor. Did you address those individually?

We’ve addressed each one differently, and we’ve adjudicated them all in different ways. Their behavior, their academics, basically every breath they take is up to my judgment on whether they’re still on this team. They’ve got to raise their cumulative averages by a half a point. They’ve got to stay out of any kind of trouble. They basically are lacrosse monks. They’ve got to be academic, behaved lacrosse guys. And so far so good, on all three of them.

We have eight kids that quit the team at the end of the year, and after investigating that, we called each and every one of them back and invited them back onto the team. Because honestly, as I said to them, I’m not proud of this fact, but I might have quit too, with all the stuff that was going down.

Dillon Roy, who’s now our only captain, quit. He was investigating going somewhere else. He had one year left, and the thing had just fallen apart. It wasn’t Jamie Munro’s fault. He did everything he could to keep it together. He was such a great guy, did such a great job here. But sometimes, new management is needed.

The thing that’s helped me here is the kids were looking for the two things I said that I would come with — communication and consistency. They would know what I wanted. It would be written out to them, stated to them; they would be treated fairly. And if there’s something wrong, I would take care of it right away.

I think they’ve been flushed of controversy. It’s a baptism, a cleansing of, “OK, we can be lacrosse players again.” For 18- to 22-year-olds, that’s all they want to be. They want to be kids. They should be kids. They want to get their degree, they want to go to a great school, but they just want to have fun a little bit. They want to play lacrosse.

And I think their fear when I was named was that this tyrant was coming in. This perception of me is so amazingly tough. I think some of them were fearful of that. What’s going to come in? Are we just going to run? Is this guy going to beat us down? Be cruel to us?

But it’s been the opposite. I’ve always said to my teams: You can create who I am. I’m just a part of this. You’re a team. You’re 44 guys. You create who we are as coaches. If you want to work hard — if you want to be taught, driven and shown how to reach the highest levels — we can do all that. If you want to be treated like babies and punished and treated badly, you can create that too. But if you want to be treated like men, then behave like men, and that’s what these guys have done so far. I’m so proud of them.

Who knows what happens if we don’t have a great year? Maybe some will say this wasn’t a good idea. But so far, so good.

The last part of this equation is the growth of the sport, specifically in the West. What was your perception of lacrosse in the West? Can you elaborate on what your vision is?

My perception came from different things. I look at what some of the guys have done out here, the Scott Hochstadts of the world that are taking these club programs in California and doing amazing things, to my experience recruiting a kid like Alex Capretta who came to Princeton last year, a California guy. I’ve had a ton of Colorado kids. My son has been here since 2001 telling me, “I’ll never come back.”

My vision of western lacrosse is it’s growing. Unfortunately right now we’re fighting something that’s bigger than me and anybody else, and that’s the issue of Title IX and finances of the growth of Division I men’s lacrosse. I’m hopeful to help this groundswell of youth lacrosse and high school lacrosse, and helping those parents and high school coaches continue to do what they do. If we can be of aid in that, we will be. We’re doing some stuff out here, expanding our programs out here, bringing some of those teams back east to show them that we can be good out here, recruiting eastern kids to come west, all that stuff.

It probably won’t happen in my lifetime, but my real goal is to get those teams and this thing to a big-time Division I level. What we’ve learned in our sport, unfortunately, is every time you take a step towards big time, it creates more problems. A long time ago, not that I’m a prophet or a soothsayer in any way, I started to sense this club thing and I said, you’ve got to be careful. Let’s not let this thing get out of hand with the club programs and people making mega bucks taking advantage of kids playing this wonderful sport. It’s happened. Some for the good, because a lot of these kids come up being better lacrosse players, but some for the bad.

I think some of what we show on TV for lacrosse right now is not good for the sport. Watching some of the guys that people look up to in lacrosse right now that are taking shortcuts, and their antics. The fighting in indoor lacrosse; the trick shot stuff; that kind of stuff, to me, isn’t helping.

But the growth out west started with kind of an X Games mentality. Isn’t this cool? I think we can mold those two things. We can keep it cool; we can keep it current; we can keep it young. I give a lot of credit to the manufacturers — the David Morrows of the world who have been at the forefront of this thing, who made it a cool thing and who bring the pro games to life. But with all that stuff, the old-timers don’t like it. Well too bad, it’s moving forward.

Recruiting is a whole other issue of your magazine. It’s not nice. It’s gone from a gentleman’s game to a backstabbing, who-can-beat-whom-to-what-punch and not liking it if they do. We’re all friends. Even in light of losing a game to a coach, no one can look at that coach and say, “Oh, what a jerk.” You lose a recruit, you go, “Whoa, what did you do to me?”

So with the growth comes some problems. My dream out west here is for people to never have to write another article against saying the Person of the Year is the Person of the Year because he came out west.

What about this Person of the Year thing?

I relate it to President Obama getting the Nobel Peace Prize. What’s he done? I haven’t done anything. I just moved from one wonderful place to another wonderful place. I’m not a big politics guy, but it was interesting to see the Russian president saying to Obama, “OK, you got this award. Now it’s a call to you to make it true in the next few years.” And I feel that call.

I don’t put all the weight on my shoulders, but if this thing is going to raise an awareness, I’ll wake up every morning knowing that. My first job is my family. My second job is my DU job. I’ve got to make this thing better. Then down the road, not much further, is, well, if you’re saying growing the sport in the West is a part of it, then you better get something done with it. And already we’re doing some free clinics for the youth coaches. We’re going to do one for the high school coaches. I’m speaking at the California convention.

Does lacrosse in the West start in Denver?

Western lacrosse starts in Pittsburgh. That’s where it starts. My daughter just became the head women’s lacrosse coach at Lebanon Valley. That’s still considered the East. But you go to Pittsburgh, you’re in the West.

Lacrosse people think you’re surfing in the Pacific when you’re in Denver. One of my best friends from Long Island is Buddy Krumenacker, the head football coach and assistant lacrosse coach at Farmingdale High School. His son John was great player at Hopkins who passed away seven years ago. He introduced me to one of his big football players who just signed with a college. “I got a scholarship to play Division I football,” he said. I said, “Where?” He said Iowa State. I said, “Awesome. Where else were you recruited?” Penn State, all the big schools at that time 20 years ago had recruited him. I said, “What made you choose Iowa State?” He said, “I always wanted to go to school on the West Coast.”

Buddy brings out a map and says, “John, this is where you’re going.” Funny, but I think of that anytime somebody says western lacrosse.

We joined the ECAC. The East Coast Athletic Conference. Talk about an oxymoron. But that’s going to mean two more of those eastern schools each year is going to come out to Denver. We’re going to play Loyola at Invesco Field.

Mac Freeman, Pat Bowlen’s right-hand man at Invesco, played at Hampden-Sydney for Ray Rostan. It all comes full circle.

Matt DaSilva

Matt DaSilva is the editor in chief of USA Lacrosse Magazine. He played LSM at Sachem (N.Y.) and for the club team at Delaware. Somewhere on the dark web resides a GIF of him getting beat for the game-winning goal in the 2002 NCLL final.

Categories

Related Articles